LGBT and Child Therapist

in Los Angeles

4 Ways to Help When You Learn About Your Child's Self-Harm

Self-harm is unfortunately more common than any parent would hope for. Almost one in five, or 17.7%, of adolescents aged 10-19 in 17 countries in North America, Australia, Europe, and Asia have participated in self-harm in their lifetime (2). In terms of gender, there is a higher prevalence among girls (21.4%) than boys (13.7%) (2).

Self-harm or non-suicidal self-injurious behavior includes actions such as cutting, scratching, scraping, squeezing or biting the skin, hair pulling, burning skin or hair, self-hitting or other actions that cause pain without the intent of killing oneself. These self-harm actions are often the result of a child wanting to regulate difficult or uncomfortable emotions. The pain is a distraction and a way of taking control.

1: Regulate Parent Emotions

The time when a parent learns about their child’s self-harm is a critical moment. Whether your child tells you directly, you discover it, or you get informed by a therapist, teacher, or other person, you want to be prepared. It’s a parental instinct to protect your child. As a result, several difficult emotions surface for the parent as shown in Figure 1 in a study by Bettis et al. in 2024 examining parental reactions when children disclosed self-harm in therapy. Sad/upset/distressed was the number one way parents reacted, followed by anxiety/worry (1). Anger/annoyance was the third most common parental reaction (1). As a parent, what’s important is processing and containing your emotions, so they don’t negatively impact your child. Containing your emotions puts you in a better position to validate your child’s self-harm disclosure to you.

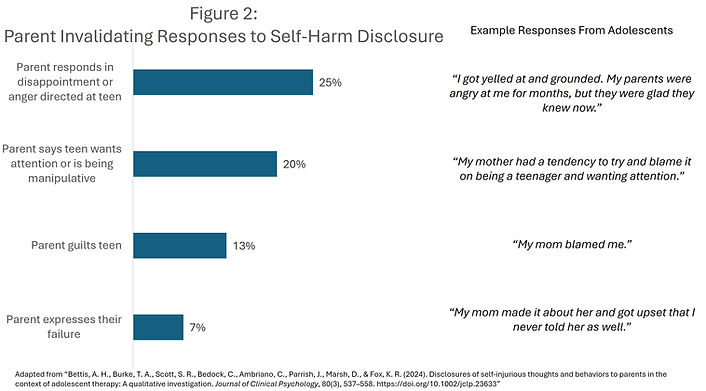

Unfortunately, parental responses to child self-harm are more commonly invalidating (1). Roughly two-thirds, or 67%, of parental responses were invalidating with disappointment or anger directed at the child being the number one response, followed by accusing the child of wanting attention as shown in Figure 2 (1). Some parents also engaged in guilting their teen for their behavior or making it about themselves and their failure to protect instead of focusing on the child (1).

Validating your child’s disclosure of self-harm is important and can be done in two key ways, helping get them support and empathizing with their emotions.

2: Find Professional Support

Helping your child get support is one of the most important steps you can take (1). In the most positive experiences of adolescents disclosing self-harm to their parents, 59% said their parents offered to get them support, while in the most negative experiences of self-harm disclosure only 20% of parents offered to get support (1). The importance of professional help is to assist with coping skills which can distract from self-harm behavior, but also help with the underlying issues of handling difficult emotions and the child’s other triggers for self-harm. If your child already has a therapist, ask the therapist about increasing support or level of care.

3: Provide Empathy

Providing emotional support and understanding, which are both forms of empathy, are the next most validating responses a parent can display as shown in Figure 4 (1). The way to empathize is to connect to what your child is feeling rather than focus on what you’re feeling or how you’re feeling for them. This even applies to talking about how you love them, which is more often experienced in a negative way for the child than a positive way (1). Show your love by asking them what they are going through and try to understand what that feels like for them.

4: Safety Plan

Once your child has disclosed self-harm to you, it’s important to create a safety plan. This is done in collaboration with the child. The benefit of a safety plan is you identify the resources that will help when everyone is calm and grounded, so when escalation starts, you don’t have to think about what to do.

The key parts of a safety plan are:

-

Triggers – identifying the warning signs of when a child might feel the urge to self-harm

-

Coping skills – identifying the activities that help the child distract from the urge to self-harm

-

Support – identify supporting people or supportive environments that can help calm the urge to self-harm

-

Safety – identify what things you can do to make your environment safer (this often involves removing items that could be used for self-harm)

-

Crisis Contacts – identify professional and crisis support that can help during a crisis if the above steps don’t work

Here’s a template for a safety plan.

If your child needs medical attention or is experiencing a crisis, call 988 or 911.

References

(1) Bettis, A. H., Burke, T. A., Scott, S. R., Bedock, C., Ambriano, C., Parrish, J., Marsh, D., & Fox, K. R. (2024). Disclosures of self‐injurious thoughts and behaviors to parents in the context of adolescent therapy: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 80(3), 537–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23633

(2) Denton E, Álvarez K. (2024). The Global Prevalence of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Among Adolescents. JAMA Netw Open, 7(6). https//doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15406